AIM — Free & Open

CC BY-NC-SAAIM is free and open for non-commercial reuse. Try a free AIM pilot (CSV + memo) — support is optional and helps sustain translations, research, and free access.

Introduction

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah stands as a defining moment in the Seerah where diplomacy, faith, and polity converged. At first glance the agreement looked like a concession: a pilgrimage deferred, clauses that frustrated companions, and public sorrow. Yet when we unpack the politics, the tribal customs that shaped negotiation, the interplay of revelation and leadership, and the long-term outcomes, the episode becomes a study in strategic patience and statecraft.

This article lays out the background, the journey to Hudaybiyyah, and the negotiation dynamics that created the written covenant known to history as The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah.

Table of Contents

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, Background and context

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, After the Hijrah the Muslim community in Medina evolved quickly from a persecuted group into a polity with administrative and diplomatic responsibilities. Earlier confrontations — notably Badr and Uhud — had forged reputations and lingering resentments between the Muslim community and the Quraysh of Mecca.

By the sixth year after Hijrah the Prophet planned a peaceful Umrah to the Kaaba. The aim was devotional but also strategic: to assert a right to worship and to demonstrate the community’s non-belligerent posture. The caravan’s non-militarized appearance — ihram attire, sacrificial animals, and a conspicuous presence of women and children — signaled intentions that were religiously motivated and politically careful.

As the group approached Mecca, Qurayshi leaders feared the political consequences of such a gathering and refused access, prompting both parties to relocate to a neutral encampment at Hudaybiyyah 1 .

The journey and arrival at Hudaybiyyah

Before The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, Approximately fourteen hundred men and women accompanied the Prophet toward Mecca. The selection of Hudaybiyyah as the negotiation site mattered: it was a neutral location where both parties could convene without immediate escalation. This was not merely a matter of geography; the decision to negotiate in a space where tribal honor and witnesses could be marshalled reflected the customary law of seventh-century Arabia.

On the Quraysh side Suhayl ibn Amr, an experienced jurist and orator, took the lead as negotiator; on the Muslim side several companions and the Prophet engaged in prolonged bargaining. The evolving diplomatic scene culminated in a written instrument — The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah — whose public recording signaled a new relational dynamic between the parties 2 .

Negotiation dynamics and diplomatic culture

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, Arabian diplomacy in this era rested on personalized honour, oath-taking, meticulous witness lists, and the social weight of writing when available. Although oral agreements were frequent, producing a written covenant with witnesses functioned as a political act that altered reputations and expectations.

Negotiations extended over days. The parties debated access to the Kaaba, the rights of those who sought asylum, mutual protections for allied tribes, and the duration of the pause in hostilities. The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah draft included clauses many companions found painful, particularly an asylum clause that seemed asymmetrical.

The Prophet accepted the written terms in spite of public disappointment, a choice later given theological validation by revelation and shown to be strategically prudent when viewed across years 3 .

The text of the treaty – main terms

Classical reports converge on a set of core stipulations that formed The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah:

- The Muslim party would return to Medina that year without performing Umrah and would be permitted to return the next year and stay three days.

- A truce lasting ten years would be observed between the parties.

- Tribes and individuals could ally themselves with either party and would enjoy the protection of that party.

- If a Meccan fled to Medina without guardian permission, they would be returned to Mecca; conversely, the Quraysh were not obliged to return a Medinan who migrated to Mecca.

- Parties agreed to respect property and to settle disputes through agreed mechanisms.

This written record converted the contest into a covenant — a public bond that brought new diplomatic possibilities and constraints 4 .

Immediate reactions and the return to Medina

The return to Medina without Umrah produced grief among many companions. Historical reports describe intense emotional responses, with Umar ibn al-Khattab’s vehemence often cited as an example of the communal angst. Into this atmosphere the Qur’anic revelation of Surah Al-Fath arrived: language referring to a “clear victory” reframed the The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah as a divinely sanctioned step, calming the community and reshaping public sentiment. This theological reframing was politically consequential, aligning devotional belief and communal strategy and validating the Prophet’s prudential stance in requesting and accepting written terms 5 .

Immediate aftermath, communications, and outreach

Following The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the Muslim leadership used the interval of peace to enlarge diplomatic horizons. The Prophet sent letters to rulers and delegations, conveying invitations and asserting the community’s presence in the regional political map. Freed from immediate hostilities, Medina could demonstrate legal practices, social norms, and the ethical comportment of its people to visiting delegations and trade caravans. This contact produced conversions and reconfigured alliances: through peaceful contact and argumentation the movement achieved social growth that would have been harder under constant warfare 6 .

Political recognition and legitimacy

The written accord represented a form of recognition: the Quraysh’s willingness to enter a covenant signalled the Muslim polity’s status as a political actor. In a society where formal agreements bore reputational consequences, such a document created diplomatic parity that enabled later alliances and negotiations. This recognition was not merely symbolic; it permitted the Prophet to engage future tribal interlocutors from a position of established legitimacy rather than a posture of insurgency 7 .

The spread of Islam and soft power gains

During the truce period the relative calm allowed traders, travelers, and tribal envoys to witness the social order in Medina firsthand. The conduct of the Muslim community, the Prophet’s measured leadership, and the persuasive clarity of the message drew conversion and affiliation that expanded the community’s social base. High-profile figures and whole tribes reconsidered their stances in light of the combined moral influence and administrative competence they observed. These soft-power gains — reputation, persuasive witness, and ethical example — complemented later military advantages 8 .

Strategic patience and the route to Mecca

One of The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah’s paradoxical outcomes was that it provided a strategic route to Mecca. Over time, shifts in alliance structures and the accrual of moral authority reduced the cost of opening political space in Mecca. When breaches of allied arrangements occurred, the Muslim polity was ready to respond; it entered Mecca in 630 CE in a manner that minimized bloodshed and maximized reconciliation. The prior diplomatic capital built around The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah helped create the conditions for a less violent resolution than many contemporaries had feared 9 .

Governance, moral authority, and reconciliation

A striking feature of the post-treaty period was the Prophet’s moral credibility. By honouring the covenant even when some terms seemed unfavourable, the Prophet strengthened his standing as a leader who adhered to principle. This moral capital proved decisive during the conquest of Mecca: clemency, measured policy, and the framing of reconciliation over vengeance enabled a smoother integration of social and religious change across the peninsula 10 .

Tactical considerations and the truce’s limits

Although designed for ten years, the truce was not indefinite: third-party actions and allied breaches eventually created circumstances that led to renewed hostilities and the eventual reconfiguration of power. Nonetheless, even a shorter period of peace delivered benefits that redounded to the Muslim polity’s advantage. The treaty’s clauses operated amid shifting social realities, and their practical enforcement depended on power dynamics — not simply on legalism — which reveals why the Prophet’s strategic patience mattered 11 .

Scholarly debates, textual traditions, and critical perspectives

Modern readers and scholars debate the meaning and fairness of particular The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah clauses. Some contemporary critiques conceive of The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah as an act of timidity; historians caution that such readings are anachronistic. Primary Arab sources — Ibn Ishaq, Ibn Hisham, Al-Tabari — present multiple narrations and variant details that require critical evaluation. Modern scholars (Watt, Donner, and others) read the event as a strategic maneuver that must be interpreted through tribal norms, the politics of reputation, and the interplay of narrative, scripture, and leadership 12 .

The asylum clause: legal history and anthropology

The asylum clause — requiring the return of Meccan runaways to Mecca while not obliging the reverse — seems asymmetrical and provoked contemporary distress. Legal historians argue the clause must be understood within the normative framework of guardianship and tribal custody that prevailed at the time. Its enforcement depended on shifting loyalties and the evolving weight of moral authority, illustrating how legal stipulations interact with social realities rather than working in a vacuum. In practice the clause’s harshness was mitigated by subsequent political developments and the spread of allegiance that altered how communities enforced or resisted the clause’s terms [1].

Practical lessons for negotiators, leaders, and communities

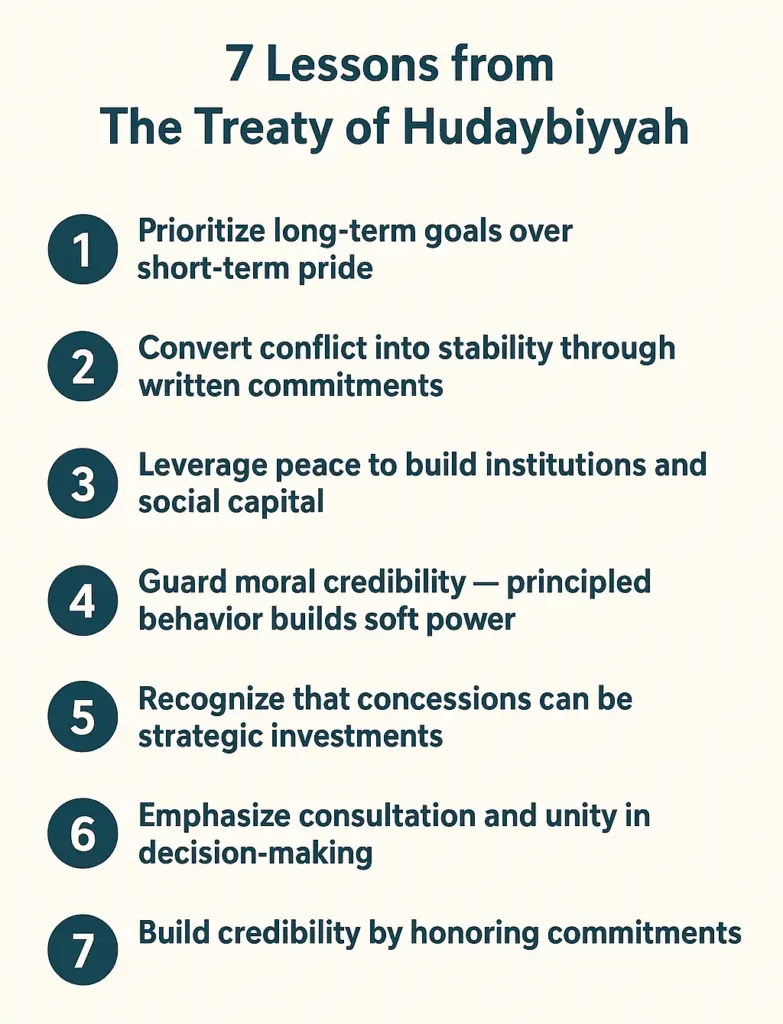

Lessons from the Seerah of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ – Leson from The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, Practical Wisdom for Today:

- Prioritize long-term goals over short-term pride

The Prophet ﷺ accepted terms that seemed unfavorable in the moment, but they secured peace and opened the door for greater future victories. - Convert conflict into stability through written commitments

Instead of endless cycles of hostility, the treaty formalized peace by writing and witnessing clear agreements — a model for sustainable conflict resolution.

- Guard moral credibility — principled behavior builds soft power

By acting ethically even under pressure, the Prophet ﷺ demonstrated integrity. This created trust, attracting allies and winning over skeptics. - Leverage peace to build institutions and social capital

The pause in fighting allowed the Muslim community to strengthen education, governance, da‘wah, and social bonds, preparing them for future expansion.

- Build credibility by honoring commitments

The Prophet ﷺ fulfilled every clause of the treaty, even when difficult. This reinforced the Muslims’ reputation for reliability, which drew more people to Islam. - Emphasize consultation and unity in decision-making

The companions initially struggled with the treaty terms, but through shūrā (consultation) and prophetic guidance, the community remained united. - Recognize that concessions can be strategic investments

What looked like compromise was actually strategy: small sacrifices led to major gains, including wider recognition of the Muslim community.

These lessons from The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, are relevant beyond late antique Arabia: diplomats, community leaders, and organizational strategists can apply the same logic of patient negotiation, legitimacy building, and institutional consolidation in modern settings.

FAQs

What was the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah and why did it matter?

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah (628 CE) was a negotiated truce between the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ and the Quraysh of Mecca. Although its terms initially appeared to favor the Quraysh, the treaty granted diplomatic recognition, created a period of peace for outreach, and ultimately enabled the steady spread of Islam through dialogue and alliances.

Why did the Prophet accept terms that seemed unfavorable at first?

The Prophet prioritized long-term strategy and moral credibility over immediate gains. Accepting the treaty reduced the risk of war, demonstrated integrity by honoring commitments, and created the peace necessary for diplomatic engagement and social influence — outcomes that proved strategically advantageous in the following years.

What practical lessons can modern negotiators learn from Hudaybiyyah?

Key lessons include:

(1) value long-term objectives over short-term pride,

(2) use credible commitments and written agreements to build trust,

(3) convert pauses in conflict into opportunities to build institutions and reputation,

(4) preserve moral credibility — honoring agreements pays strategic dividends.

Chronology & Timeline – concise

- 628 CE / 6 AH: Muslims approach Mecca and negotiations proceed at Hudaybiyyah.

- Treaty signed; Muslims return to Medina without performing Umrah that year.

- Shortly after: the Qur’anic revelation of Surah Al-Fath reframes the event as part of a larger divine strategy.

- Circa 630 CE: changing alliances and breaches create circumstances that lead to a largely peaceful entry into Mecca.

Final reflections

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah is a paradigmatic story of how leadership, law, and faith intersect to produce outcomes that are not immediately obvious. What appeared to be a concession at the time matured into a platform for stability, outreach, and moral reconciliation. For Muslims, it is a moment of prophetic wisdom reinforced by revelation; for non-Muslims it is an instructive case in negotiation, soft power, and the conversion of reputational capital into political advantage.

References

- Ibn Ishaq / Ibn Hisham, The Life of the Prophet (al-Sirah al-Nabawiyyah).

The foundational early biography that compiles oral reports and early narratives about the Prophet’s life. Ibn Hisham’s redaction is commonly used by scholars and translators; consult critical notes and comparative editions to trace variant readings and chains of transmission. ↩︎ - Al-Tabari, Tarikh al-Rusul wa-l-Muluk (History of the Prophets and Kings).

A major medieval chronicle preserving multiple narrations and viewpoints. Tabari’s compilation collects variant reports and isnads, making it important for assessing divergent traditions and the historiographical texture around Hudaybiyyah. ↩︎ - Ibn Kathir, Al-Bidaya wa-l-Nihaya and Seerah commentary.

Classical narrative and exegetical work that ties Qur’anic verses to historical episodes. Ibn Kathir’s synthesis offers a traditional reading valuable for linking Surah Al-Fath to the treaty context. ↩︎ - Montgomery Watt, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman.

A modern scholarly treatment emphasizing the political and diplomatic strategies of the Prophet’s life. Watt situates Hudaybiyyah within broader statecraft and offers analytical frameworks useful for non-specialist readers. ↩︎ - Karen Armstrong, Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time.

A readable biography for general audiences that places events like Hudaybiyyah within moral and historical perspective, useful for making the episode accessible to non-Muslim readers. ↩︎ - Akram Diya al-Umari, Ar-Raheeq al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar).

An award-winning modern seerah that compiles primary traditions into a clear and concise narrative, helpful for quickly locating the main events and conventional chronology. ↩︎ - Fred Donner, Muhammad and the Believers.

Academic analysis of early community formation, showing how treaties and pacts functioned in the politics of group consolidation. Donner’s work is valuable for comparative and theoretical readings. ↩︎ - Reza Aslan, No God but God.

A narrative history that helps readers trace broader transformations in early Islam and the sociopolitical currents that contextualize events like Hudaybiyyah. ↩︎ - Seyyed Hossein Nasr (ed.), The Study Quran.

An annotated translation with essays and commentary; particularly useful for understanding Surah Al-Fath and its interpretive implications for the treaty. ↩︎ - Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim — selected hadiths about Hudaybiyyah.

Core hadith collections preserving many companion reports. For historical work, consult critical translations and scholarly commentary that examine isnad reliability and transmission. ↩︎ - Academic journal articles on Arabian tribal diplomacy and law.

Peer-reviewed articles examine asylum clauses, guardianship norms, and the material conditions underpinning treaty clauses in the seventh century. These provide anthropological, legal, and comparative perspectives. ↩︎ - Encyclopaedia of Islam entries and modern peer-reviewed syntheses.

Authoritative summaries that point toward primary editions, variant traditions, and up-to-date bibliographic leads in several languages for further reading. ↩︎

Discover more from Ahmed Alshamsy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.