AIM — Free & Open

CC BY-NC-SAAIM is free and open for non-commercial reuse. Try a free AIM pilot (CSV + memo) — support is optional and helps sustain translations, research, and free access.

Use a disciplined, six-step method to reflect on a Quranic verse: How to Read a Verse? read slowly, check immediate context, study key words and grammar, consult classical tafsir, consider historical context cautiously, and reflect on contemporary application with humility. This approach helps both Muslim and non-Muslim readers avoid common mistakes while learning responsibly 1 2 .

Introduction – why a method matters

The Quran is read as scripture, law, poetry, and spiritual guidance across many languages and cultures. That wealth of meanings is a strength, but it also makes quick readings risky: verses taken out of context, used as proof-texts, or translated without attention to language nuance can easily mislead readers and listeners [1] 3 . A short, repeatable method helps readers slow down, check their assumptions, and draw more balanced conclusions. The six-step approach below synthesizes classical exegetical practice and modern reading principles so you can approach verses respectfully and with intellectual humility [2] 4 .

How to Read a Verse? Who this guide is for (and when to consult experts)

This guide is for curious readers — Muslim and non-Muslim — who want a principled process for approaching a verse; for students beginning Quranic study; and for facilitators who wish to model careful exegesis in public conversations. It is not a substitute for formal scholarly training or for consulting qualified jurists when a verse touches legal rulings or complex doctrinal questions [2] 5 . When a verse intersects with communal policy or law, seek multiple qualified scholarly opinions rather than issuing a final judgment on your own [2] 6 .

Overview – the 6 practical steps

- Read slowly — original Arabic if possible and at least two reputable translations. [3]

- Check immediate literary context — surrounding verses and surah structure. [4]

- Study key words and grammar — roots, morphology, and rhetorical devices. [5]

- Consult classical tafsir — compare a few reputable commentators. [2][6]

- Consider historical context (asbāb al-nuzūl) cautiously — corroborate reports. [7]

- Reflect on contemporary application — extract principles, act with humility. [8]

Step 1 – Read slowly: multiple passes, multiple translations

How to Read a Verse, Start by slowing down. Read the verse three times: first for general sense, second for wording and cadence, third for what emotionally or rhetorically stands out. If you can read Arabic, hear the verse aloud to sense rhetorical devices; if you read translation only, compare at least two reputable translations to notice differences in word choice [3].

Actionable tips:

- Read the verse in the original Arabic when possible; if not, read two translations (one literal-ish, one idiomatic) to notice translator choices. [3]

- Mark words or phrases that feel ambiguous, emphatic, or repeated; you’ll analyze them in Step 3.

- Note whether the language reads as command, narrative, parable, or exhortation — tone matters.

Why this helps: many misreadings come from skimming. Slow, repeated reading reveals grammatical cues, rhetorical rhythm, and the emotional weight of words that a cursory glance misses [3][5].

Step 2 – Check immediate literary context

How to Read a Verse, A verse rarely stands isolated. Pronouns, narrative subjects, and rhetorical flows often depend on the preceding and following lines [4]. Always ask: what is the immediate passage doing? Is this a part of a story, a legal section, a moral exhortation, or a parable?

Actionable tips:

- Read at least the surrounding 6–12 verses and summarize that short passage in one sentence. [4]

- Identify referents (who is “they,” “you,” or “we” in this passage?).

- Note shifts in subject or audience — is the divine address singular, plural, or rhetorical?

Why this helps: context clarifies whether a verse was situational (addressing a moment) or offering a general principle. Removing context can invert meaning or strip nuance [4] 7 .

Step 3 – Study key words and grammar (language matters)

How to Read a Verse, Arabic words carry semantic fields shaped by triliteral roots; verb forms and particles carry important nuance. A literal-looking translation may hide a richer semantic range.

Actionable tips:

- Identify 3–5 core words in the verse and check root meanings and common usages. Use a reliable lexicon or translators’ notes if you don’t read Arabic. [5]

- Note verb forms (imperative vs. jussive), particles (e.g., inna, laʾ, ma), and pronoun attachments.

- Record alternative translations and what each choice implies.

Why this helps: a single word’s grammatical form or root can change whether a verse reads as descriptive, prescriptive, general, or conditional. Language study reduces oversimplified readings [5].

Step 4 – Consult classical tafsir (2–4 sources)

How to Read a Verse, Tafsir literature collects early readings, narrations, linguistic arguments, and legal inferences. Consulting tafsir situates your reading within a tradition and reveals how different communities understood the verse [2][6].

Actionable tips:

- Start with one or two classical tafsir (e.g., Ibn Kathir, Al-Tabari summaries) and one modern commentary or academic primer to balance perspectives. [2][6]

- Summarize each tafsir’s main point in one sentence and note whether it uses historical reports, hadith, or grammatical argument.

- Where tafsir disagree, note the grounds: history, language, jurisprudence, or moral emphasis.

Why this helps: tafsir shows interpretive history and stabilized readings; differences among commentators tell you which elements are settled and which remain debated 8 9 .

Step 5 — Consider historical context (asbāb al-nuzūl) cautiously

How to Read a Verse, Occasions of revelation can explain why a verse uses certain words or addresses particular people, but not every verse has a robust single-cause report, and some reports are weak or contested [7].

Actionable tips:

- If an asbāb report is cited in tafsir, check whether it is widely attested and whether modern scholarship treats it as reliable. [7]

- Use historical context to clarify referents, not to force a narrow reading when broader principles are plausible.

- Be cautious with single-chain reports; corroboration strengthens historical claims.

Why this helps: historical reports, when reliable, prevent categorical misapplications of a verse; but over-reliance on doubtful reports can unduly narrow ethical implications [7][9].

Step 6 — Reflect on contemporary application with humility

How to Read a Verse, After careful reading, ask: what core principles emerge, and how might they apply in present circumstances? Avoid forcing a political or legal program onto a single verse. Instead, extract ethical or spiritual principles and propose modest, practical applications [8].

Actionable tips:

- Identify 1–3 principles (e.g., mercy, justice, patience). For each, suggest one concrete practice a reader can try this week. [8]

- When sharing your reading publicly, state limits: “This is my reading; other scholars read differently.” Invite correction and dialogue.

- For community policy or law, consult qualified scholars across traditions before acting.

Why this helps: humility keeps interpretation open to correction and reduces dogmatism. Good applications respect the text’s complexity and the community’s interpretive traditions [2][8].

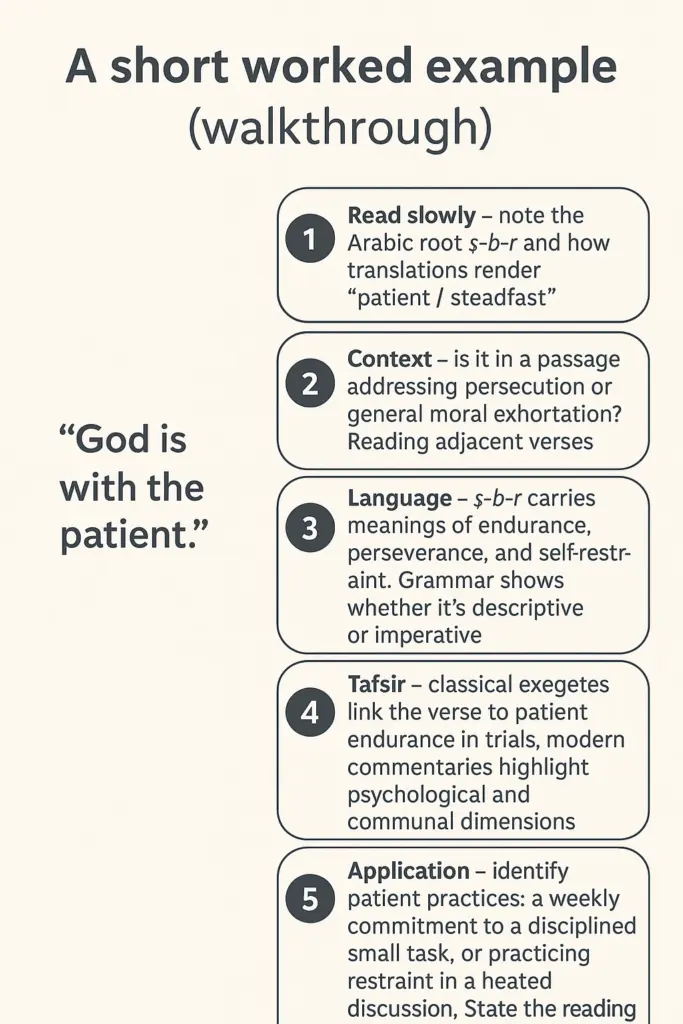

A short worked example (walkthrough)

How to Read a Verse, Take a familiar, short verse (paraphrased): “God is with the patient.” Apply the steps quickly:

- Read slowly — notice the Arabic root ṣ-b-r and how translations render “patient / steadfast.” [5]

- Context — is it in a passage addressing persecution or general moral exhortation? Reading adjacent verses clarifies the tone. [4]

- Language — ṣ-b-r carries meanings of endurance, perseverance, and self-restraint. Grammar shows whether it’s descriptive or imperative. [5]

- Tafsir — classical exegesis link the verse to patient endurance in trials; modern commentaries highlight psychological and communal dimensions. [6]

- Historical context — if tied to an episode, the occasion enriches meaning but does not eliminate its general moral force. [7]

- Application — identify patient practices: a weekly commitment to a disciplined small task, or practicing restraint in a heated discussion. State the reading as one helpful perspective, not the only one. [8]

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

- Proof-texting: Don’t use a single verse as a final answer to complex modern legal or political questions. Consult a range of sources and experts. [2][9]

- Selective quoting: Avoid removing verses from surrounding text; doing so can invert meaning. [4]

- Over-reliance on weak reports: Check the strength and corroboration of historical reports before building major claims on them. [7]

- Ignoring interpretive plurality: Recognize that multiple, well-grounded interpretations can coexist; note disagreements rather than erase them. [6][9]

An 8-week study plan to build skill and humility

Week 1–2: Daily short readings — pick 8 concise verses and apply Steps 1–3; keep a small journal. [3][5]

Week 3–4: Add tafsir — for four verses consult 2–3 tafsir and record differences in a table. [2][6]

Week 5–6: Explore asbāb al-nuzūl for two verses and assess the reliability of reports. [7]

Week 7: Draft short application notes (one paragraph each) that translate meaning into a daily practice. [8]

Week 8: Share one reflection in a study group or online forum, invite corrections, and revise accordingly. This iterative public feedback builds both scholarship and humility. [2][8]

Responsible online research & tools

- Prefer academically reputable translations and printed tafsir with editorial introductions; library and university resources are reliable starting points. [3][6]

- Use lexicons and language tools to check root fields; for non-Arabic readers, translators’ notes and academic summaries are invaluable. [5]

- Treat social media posts and forum claims as opinions until primary sources or peer-reviewed scholarship confirm them. [9]

FAQs

Do I need Arabic to reflect on a verse?

No. You can begin with reliable translations and commentaries. Learning Arabic deepens study but is not required for reflective engagement. [3][5]

How many tafsir should I consult for a balanced reading?

At least two — one classical and one modern or accessible academic commentary — then widen reading when tafsir diverge. [2][6]

What if tafsir disagree sharply?

Record the grounds of disagreement (history, grammar, legal method) and present multiple readings; divergence often reveals interpretive richness rather than error. [6][9]

References & Further Reading

- Pew Research Center — global religious demography and analyses on Muslim population growth and diversity; background for why careful reading across audiences matters. ↩︎

- Classical and modern tafsir introductions — overviews explaining tafsir methods and the role of exegetical traditions in interpretation. Good introductory works and course notes offer methodological grounding. ↩︎

- Reliable translations with notes: M. A. S. Abdel Haleem (“The Qur’an: A New Translation”), Muhammad Asad (“The Message of the Qur’an”), Mustafa Khattab (The Clear Quran) — recommended for comparative reading and translation notes. ↩︎

- Studies on literary context and Quranic structure — analyses showing how immediate context affects verse meaning and the problems with isolated quotations. ↩︎

- Arabic lexical and grammatical sources — Lane’s Lexicon (classic) and modern learner lexicons; resources that explain triliteral root semantics and grammatical forms. ↩︎

- Selected tafsir sources (classical & modern): Ibn Kathir (abridged translations), Al-Tabari (selections), and accessible modern commentaries that balance historical reports with linguistic analysis. ↩︎

- Scholarship on asbāb al-nuzūl (occasions of revelation) — works that outline the strengths and limits of using reported occasions for interpretation, and how to evaluate report reliability. ↩︎

- Ethical and practical applications literature: thematic readings (e.g., Fazlur Rahman’s thematic studies) and guides on applying scriptural principles to modern life responsibly. ↩︎

- Academic primers and critical studies — articles and textbooks that present modern scholarly debates about Quranic interpretation, historical-critical approaches, and methodological cautions. ↩︎

Discover more from Ahmed Alshamsy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.